Explore how the (new) web browser AI wars are redefining user privacy, security features and what you need to know to stay safe.

Table of Contents

For years, web browsers were static gateways to an expanding digital world. They accompanied our transition from desktop to cloud, from blog to streaming, and from forum to social network, without changing too much in their essence. To browse was to type, wait, and click. Nothing else. But, as so often happens with technology, what seemed stable has begun to mutate, quietly at first, more obviously now.

The new generation of web browsers is not satisfied with taking us from one place to another: they want to do it for us. Decide, filter, execute. It anticipates our intentions and acts accordingly. And that ambition, which would once have seemed like science fiction, has given rise to a new conflict. A different war, not for speed or compatibility, but for agency. To know which software will decide on our behalf what deserves our attention.

The curious thing, and perhaps the most significant thing, is that this battle is not being fought by the usual suspects. There is no trace of Chrome, Edge, Safari, or Firefox. The protagonists are others—smaller, more agile, and more willing to break molds. And while the big ones watch from the rearguard, three names are already vying for first place in a completely new category: that of browsers built from the ground up to function as artificial intelligence agents.

The Web Browser AI Wars of the Past: From Netscape to Chrome

Before talking about the new war, it is worth remembering that this is not the first. Web browsers have been involved in some of the most intense and strategic technological clashes in the history of the Internet. The first major conflict broke out in the 1990s, after Mosaic, when Netscape Navigator dominated online browsing and Microsoft decided to integrate Internet Explorer into Windows. That didn’t just upset the market balance: it laid the groundwork for how big companies could shape the web in their image.

The fall of Netscape ushered in a second era of conflict. Firefox emerged as a reaction, as an attempt to recover the openness and lightness lost. For a while, it managed to consolidate itself as a solid alternative. But then along came Chrome. Fast, minimalist, and backed by Google’s technical muscle, the Mountain View browser quickly conquered market share. With it also came far-reaching structural decisions: the rise of the Blink engine, the fall of alternative standards, and a certain homogenization of the web experience.

The third war was quieter, but no less relevant. Edge, reborn on Chromium, tried to regain the ground lost by Microsoft. Brave bet on privacy and decentralization. Safari remained firmly within the Apple ecosystem. But Chrome’s hegemony was never seriously threatened. The model was consolidated: navigator as a neutral platform, passive window, functional tool.

And now, when it seemed that everything was resolved, a new front is emerging. It is not a question of which browser loads faster, nor which consumes less RAM. The battle is shifting to another terrain: that of artificial intelligence that not only assists but also acts. A transformation that not only reopens the competition but also redefines its rules.

What Are Agentic Web Browsers (And Why Do The Rules Change)?

The term sounds technical, but its implication is profound. An agent browser is not simply an “AI” browser, like those that already integrate chats, summaries, or assistants. It is a tool built from the ground up to function as an autonomous agent: an artificial intelligence capable of understanding orders, making decisions, and executing actions within the web on behalf of the user.

The difference is substantial. While browsers such as Edge or Brave offer built-in assistants—useful but passive—agent browsers incorporate a radically different operating logic. They don’t just respond; they act. They analyze the content of a page, detect interactive elements, interpret the user’s intent, and perform specific tasks. Search, filter, compare, fill out forms, buy, schedule, plan trips… all without the user having to actively navigate multiple tabs or interfaces.

This type of navigation transforms the user’s role from active explorer to high-level supervisor. Interaction no longer depends on the click but on the declared intention. The agent browser translates that intention into a chain of actions, executed on the very structure of the web. It does not “visit” pages as before but interprets them, extracts what is useful, and, in many cases, acts on them without showing anything in between.

The implications are enormous. On the one hand, the efficiency promises to be extraordinary: less wasted time, less friction, and more results. On the other, it raises new questions about privacy, transparency, security, and control. To what extent do we know what AI is doing for us? What happens if you act badly or if you make wrong decisions? In this new war, it is not only technology that changes. It changes the very nature of sailing.

Opera Neon: the European pioneer

Announced in mid-2025 and recently arrived in Spain, Opera Neon is presented as the first browser specifically designed under an agentic logic. This is not a traditional browser with added features but a tool built from the ground up so that artificial intelligence not only assists but also acts on behalf of the user. Opera doesn’t hide it: its proposal is designed for those who work, study, or spend a lot of time in front of the web and are looking for more than just a navigation interface.

The heart of Opera Neon are the so-called Tasks, independent spaces that replace the classic concept of the eyelash. Each task represents a specific intention or project: to compare products, to research a topic, or to plan a trip. Within that context, the browser understands what the user wants to do and executes actions that previously required multiple manual steps. Open and close tabs, fill out forms, collect data, structure information… everything can be done from AI, in real time and in a visible way.

To further facilitate this modular approach, Neon incorporates Cards, fragments of instructions that can be reused, combined, and adapted as needed. There are cards to compare prices, take notes, generate tables, automate searches, or create reports. The user can build their own or take advantage of those shared by the community. It is a way of providing the browser with a command language that replaces the traditional interaction based on clicks and menus.

One of the most prominent elements of the system is Neon Do, a specific feature that allows the browser to execute practical tasks within each task. It doesn’t just suggest or show; it acts. And it does so without the need to send sensitive data to the cloud or share passwords. AI operates on the page structure directly, processing the DOM tree to make informed, not improvised, decisions.

Opera Neon is available under a subscription model, and initial access is by invitation. A strategy that clearly aims at an advanced audience, which already trusts AI as an everyday tool. Its launch marks a before and after: for the first time, a web browser is no longer a passive viewer and becomes an autonomous action environment, where navigation is only one of the possible outcomes.

Comet: Perplexity’s bet

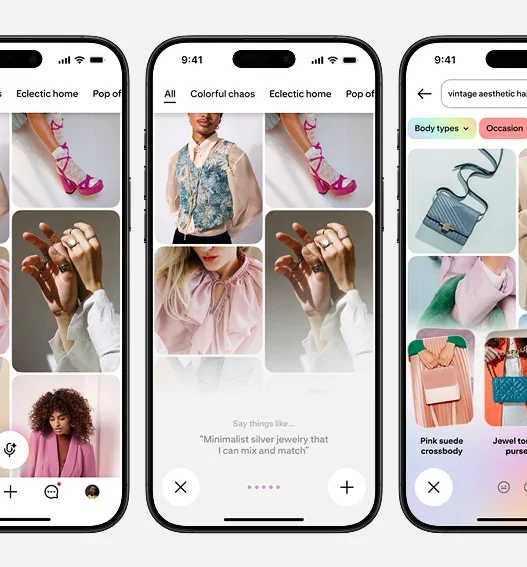

In an environment dominated by browsers that limit themselves to showing, Comet proposes a radically different approach: understand, act, and accompany. Perplexity’s browser, fresh out of the incubator, not only integrates artificial intelligence but also redefines the model of interaction with the web. Its stated goal is to end the tab chaos and transform browsing into a continuous flow of thought.

At first glance, Comet does not impose. It inherits the clean aesthetics of any modern browser and maintains classic elements such as the address bar, tabs, and navigation buttons. But its real difference lies in the left sidebar: an AI assistant that not only answers questions but also executes complex actions based on natural language instructions. The user does not navigate between tools; he talks to a single one who does everything.

In one demonstration, the navigator interprets a command to map out a tourist route through London. Without changing the window, select the starting location, plan the route, and present it directly on the open map. In another example, you can summarize a discussion on Reddit, search for a specific video, compose an email with the information visible on the screen, or even retrieve content read days ago. Everything happens within the browser, with no extensions, no jumps, and no friction.

Perplexity’s approach goes beyond conversation: it wants the browser to think like we do. Comet seeks to learn from the user’s cognitive style—how they ask questions, what topics interest them, when they change focus—to fine-tune interaction and anticipate needs. That fluidity is not meant to be magical but precise. The company insists that its priority is not only speed but also the quality and reliability of the responses, understood as the basis for making better decisions.

To achieve that precision, Comet allows granular interactions: highlighting a text and asking for an immediate explanation, exploring related concepts without abandoning what is being read, and asking for counterarguments or cross-references. It is a browser that not only displays content but also proposes relationships, structures, and paths of thought. A cognitive agent rather than a query tool.

This ambition, however, is not gratuitous. Comet needs to know the user thoroughly to fine-tune their behavior. And that raises inevitable questions about privacy, habit following, and ethical boundaries. To what extent are we willing to give up cognitive space to software that aspires to think with us?

Atlas: OpenAI enters the scene.

OpenAI has not been satisfied with ChatGPT being an external tool to the browser: it has decided to turn it into the browser itself. With Atlas, the company behind GPT-5 proposes a browsing experience fully integrated with its artificial intelligence, where each step, each tab, and each piece of text can be contextualized and assisted by its most advanced model. It’s not just an AI browser; it’s a browser designed around AI.

Atlas is based on Chromium, which guarantees compatibility with most websites, Chrome extensions, and current technical standards. Its appearance is not too different from that of a conventional browser, but the change is noticeable when you interact: instead of using Google or another search engine, new tabs directly open ChatGPT, with AI-generated responses in the foreground and web results accessible in secondary tabs. AI doesn’t just search; it also explains, synthesizes, and compares—all without leaving the Atlas environment.

One of its most powerful features is contextual integration. While browsing, the user can activate a side panel to consult ChatGPT about the content of the active page. It is also possible to select text and, from the context menu, ask for clarifications, definitions, or summaries. The model acts as a reading companion that is available at any time, without interrupting the flow of navigation.

But the real novelty is in the integrated memory. Atlas can remember preferences, styles, frequent topics or search habits, and adapt its answers to that cognitive profile. If the user works in technological dissemination, for example, the browser will know how to simplify explanations when necessary. If you’ve been comparing laptops for a while, you can incorporate old data into new searches. These “facts” are stored as editable elements and are managed from ChatGPT’s memory, allowing unprecedented continuity between sessions.

OpenAI has taken privacy precautions: AI does not access the content of pages unless explicitly allowed by the user, and it never interacts with passwords, messages, or sensitive data. Navigation is processed locally, and only by activating the AI dashboard does contextual interaction occur. Still, Atlas’ potential to cement a deeply personalized browsing experience opens up new debates about the balance between convenience and control.

For now, Atlas is only available for macOS and requires logging in with a ChatGPT account. But the message is clear: OpenAI wants its model to stop being a one-off tool and become the reference framework for interacting with the web. And with Atlas, he takes a decisive step towards that goal.

Where are the big ones?

There is something striking about this new war of web browsers: its protagonists are not the same as always. Neither Chrome nor Safari nor Edge nor Firefox has yet made the leap to fully agentic browsing. None have featured a browser built from scratch with artificial intelligence as the functional core. The revolution does not come, for now, from the big platforms, but from their margins.

Google, whose browser dominates the market with an iron fist, has integrated its Gemini model into Chrome, but it does so in a half-hearted way. The user continues to browse in a traditional way, and the AI is limited to offering summaries or suggestions. Microsoft, with Copilot in Edge, has gone a little further but maintains the navigation model focused on tabs and links. Safari, on the other hand, remains in a functional conservatism, prioritizing privacy and efficiency over agentic exploration.

Why this caution? In part, by inertia: when you dominate the market, moving pieces involves risks. But also for strategic reasons. Chrome and Edge are deeply tied to business models based on advertising, user tracking, and organic positioning. A browser that acts directly on the content, that summarizes and decides for the user, reduces the visibility of ads, weakens SEO, and threatens the commercial architecture of a large part of the current web.

In addition, traditional browsers carry technical legacies and expectations of millions of users that make radical reinvention difficult. It’s not the same to launch a new tool from scratch as it is to redesign the behavior of a platform with hundreds of extensions, configurations, and dependencies.

Meanwhile, Opera, Perplexity, and OpenAI allow themselves to experiment. They don’t have so much to lose, and they do have a lot to gain. Its proposals do not compete to be the “fastest” or the “most compatible,” but to be the first to offer a new way of sailing. In that strategic vacuum that the big guys have left, an opportunity has opened up for others to rewrite the rules.

A New Battlefield: What’s at Stake

In this new war of web browsers, there is no dispute about a change of rendering engine, nor a more minimalist interface, nor even a stricter privacy model. What’s at stake is something much more fundamental: who controls the browsing experience and how the architecture of the web itself is transformed.

Agent browsers don’t just display pages. They process them, interpret them, summarize them, and filter them. Often, they decide which parts to show and which to ignore. In some cases, such as Opera Neon or Comet, the user does not even see the original content: they receive a processed response, an action executed, or a decision made. What happens then with web design, with SEO, with ads, with the structure that until now guided the user’s attention?

If this trend prevails, many websites will stop competing for clicks and will start to do so because they are understood by an AI. Optimization will no longer be for humans but for agents. Interfaces will no longer matter if the browser never displays them. Superficial content will be penalized not for its aesthetics, but for its cognitive inefficiency. Everything will revolve around how an AI interprets, synthesizes, and executes.

For the user, the promise is attractive: less noise, fewer steps, more results. But it also implies a transfer of control. Instead of exploring, we delegate. Instead of choosing, we ask. The browser, which for decades was a passive window, now becomes an active filter, even a biased interlocutor. And with this, the relationship between us and information changes irreversibly.

This new war redefines not only what browsers we use, but also what we mean by browsing. Because if we no longer open links or read pages, is it still navigation? Or are we witnessing the birth of something else: a cognitive layer on the web, managed by agents who think, act, and filter for us?

Specific risks of agentic browser

Any technology that multiplies its operational power also expands its risk surface. Agent browsers, by definition, leave behind the passivity of classic browsers and enter the field of execution. They don’t just interpret the web; they act on it. And that makes them tools as powerful as they are potentially dangerous.

One of the most studied risks is the so-called indirect prompt injection. Unlike classic malware, this attack does not require executable code but simple instructions camouflaged in web pages. The browser, when analyzing them, can interpret them as legitimate commands: send data, alter forms, and open unauthorized sessions. In a system where AI acts for us, a phrase embedded in the right place can have disproportionate consequences.

Another risk is that of excess privileges. By acting with the same permissions as the user, an agent browser can access—and in some cases manipulate—sensitive information: banking forms, educational platforms, webmail, and online applications. The line between helping and pushing its limits can easily be blurred if there are no clear technical barriers.

Nor can the risk of “memory poisoning” be ignored. If the browser remembers habits, preferences, or events over time, what happens if someone manages to manipulate that memory? Repeated malicious instructions or falsified contexts could alter the agent’s behavior, generating bias, losing accuracy, or compromising decisions.

And, of course, there’s privacy. To act efficiently, the browser must analyze what the user sees, what they do, and what they search for. Even if manufacturers claim that data is not shared, the very logic of the system requires constant monitoring of the context. It’s a delicate balance between assistance and surveillance, between contextual help and mass data collection.

Some solutions are beginning to take shape: separation of roles between interface and execution, human supervision in critical tasks, and use of virtualized environments for agent actions. But the truth is that we are still in an early phase, and that these browsers, as useful as they are, open doors that we are not always prepared to cross.

Sailing is not what it used to be (and the tomato no longer tastes like a tomato)

For years, browsing the internet was essentially a manual experience. We decided what to look for, which page to go to, what to read, and what to ignore. Web browsers were silent witnesses to this process: they opened windows but never crossed them by us. Now, with the agentic browsers, all that is starting to change. Navigation is no longer an action but a delegation. We don’t sail; we ask to be taken.

There is something fascinating about this evolution. That a browser remembers our habits, understands our doubts, acts for us, and even anticipates what we are going to need sounds, in many ways, like the next logical step. But there is also something disturbing. Because in that transit, we run the risk of losing our compass, of giving up more than we want and should, of letting others—even without a face—decide for us what deserves our attention.

I’m not sure if this is the best possible version of the future of the web, but I do know that it marks a turning point. And as in every previous browser war, not only will the tools change, but the user will change. What was once an open window to the world can now become a mirror that gives us back what we think we need or what someone has trained us to believe we need. Perhaps that is why this war is more important than the previous ones. Because it doesn’t just discuss code, speed, or design. Discuss how we think, how we decide, and how we trust.

FAQ from Content

Q1. What are the “new web browser AI wars”?

A1. The “new web browser AI wars” refer to the competition among major browsers like Chrome, Edge, Safari, and Brave to integrate advanced AI tools that enhance user experience, speed, and personalization.

Q2. How are AI-powered browsers impacting online privacy?

A2. AI in browsers can improve privacy by detecting malicious sites and blocking trackers, but it also raises concerns about data collection and algorithm transparency.

Q3. What security improvements have emerged from AI browser competition?

A3. AI-driven browsers now offer real-time phishing protection, smarter password management, and predictive threat detection, enhancing overall user security.